Make America Great Again Muslim Head Scarf

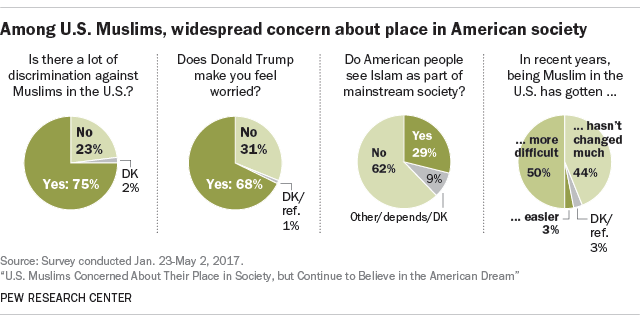

The early days of Donald Trump'southward presidency have been an anxious time for many Muslim Americans, co-ordinate to a new Pew Inquiry Center survey. Overall, Muslims in the U.s.a. perceive a lot of bigotry confronting their religious grouping, are leery of Trump and think their swain Americans exercise not meet Islam as part of mainstream U.S. lodge.

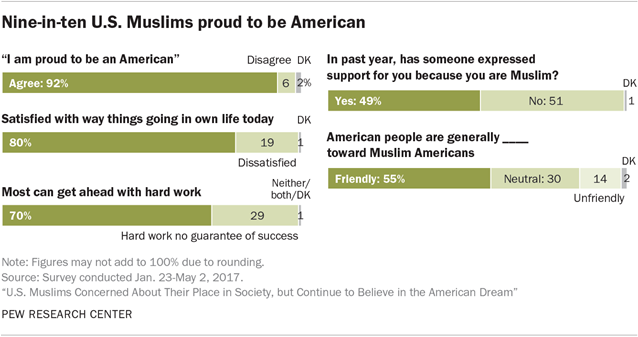

At the aforementioned time, however, Muslim Americans express a persistent streak of optimism and positive feelings. Overwhelmingly, they say they are proud to exist Americans, believe that hard piece of work generally brings success in this country and are satisfied with the way things are going in their own lives – even if they are not satisfied with the management of the country every bit a whole.

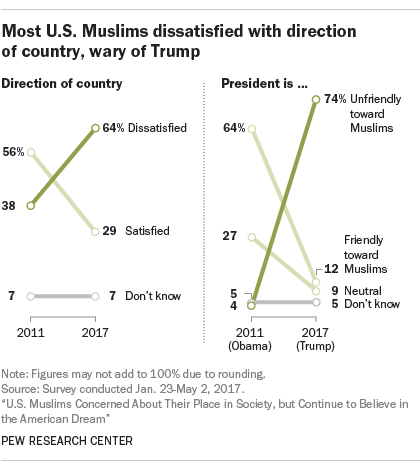

Indeed, nearly two-thirds of Muslim Americans say they are dissatisfied with the mode things are going in the U.S. today. And about 3-quarters say Donald Trump is unfriendly toward Muslims in America. On both of these counts, Muslim stance has undergone a stark reversal since 2011, when Barack Obama was president, at which betoken nigh Muslims thought the state was headed in the right direction and viewed the president equally friendly toward them.

Indeed, nearly two-thirds of Muslim Americans say they are dissatisfied with the mode things are going in the U.S. today. And about 3-quarters say Donald Trump is unfriendly toward Muslims in America. On both of these counts, Muslim stance has undergone a stark reversal since 2011, when Barack Obama was president, at which betoken nigh Muslims thought the state was headed in the right direction and viewed the president equally friendly toward them.

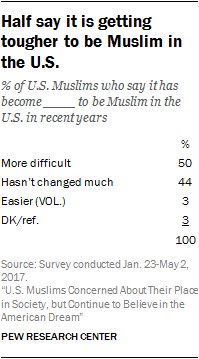

In addition, half of Muslim Americans say it has become harder to be Muslim in the U.South. in recent years. And 48% say they take experienced at to the lowest degree one incident of discrimination in the by 12 months.

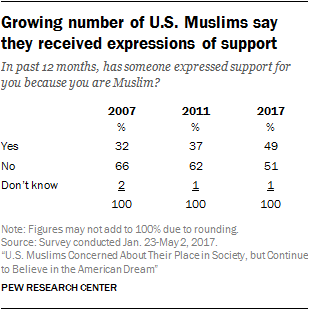

But aslope these reports of discrimination, a like – and growing – share (49%) of Muslim Americans say someone has expressed support for them because of their religion in the past year. And 55% think Americans in full general are friendly toward U.Southward. Muslims, compared with just fourteen% who say they are unfriendly.

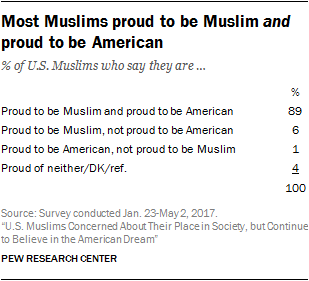

Despite the concerns and perceived challenges they face, 89% of Muslims say they are both proud to be American and proud to be Muslim. Fully viii-in-ten say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their lives. And a large majority of U.S. Muslims continue to profess faith in the American dream, with 70% saying that most people who desire to get ahead tin can make information technology in America if they are willing to work hard.

These are amidst the fundamental findings of Pew Enquiry Eye's new survey of U.S. Muslims, conducted Jan. 23 to May 2, 2017, on landlines and cellphones, among a representative sample of 1,001 Muslim adults living in the U.s.a.. This is the tertiary fourth dimension Pew Research Heart has conducted a comprehensive survey of U.S. Muslims. The Center's initial survey of Muslim Americans was conducted in 2007; the second survey took place in 2011.

The new survey asked U.S. Muslims about a wide diverseness of topics, including religious beliefs and practices, social values, views on extremism and political preferences. While the survey finds that a majority disapprove of the way Trump is handling his job, this is not the first time the community has looked askance at a Republican in the White Firm. Indeed, Muslim Americans are no more than disapproving of Trump today than they were of George West. Bush's performance in part during his 2d term a decade ago.

And while Muslims say they face a variety of challenges and obstacles in the U.S., this too is zip new. The share of U.S. Muslims who say it is getting harder to be a Muslim in America has hovered around fifty% over the past 10 years. Over the same period, half or more than of Muslims have consistently said that U.S. media coverage of Muslims is unfair.

The Muslim population in the U.S. is growing and highly diverse, made up largely of immigrants and the children of immigrants from all across the world. Indeed, respondents in the survey hail from at to the lowest degree 75 nations – although the vast bulk are at present U.Due south. citizens. As a group, Muslims are younger and more racially various than the general population.

Muslims besides are quite varied in their religious allegiances and observances. Slightly more than one-half of U.South. Muslims are Sunnis (55%), simply significant minorities identify equally Shiite (16%) or every bit "just Muslim" (xiv%). Well-nigh Muslims say religion is very important in their lives (65%), and well-nigh 4-in-10 (42%) say they pray five times a mean solar day. But many others say religion is less important to them and that they are non so consistent in performing salah, the ritual prayers that constitute one of the Five Pillars of Islam and traditionally are performed v times each twenty-four hour period.

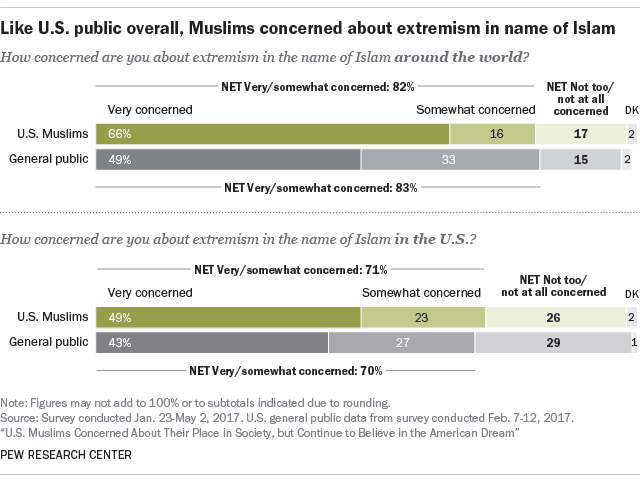

The survey also shows that Muslims largely share the full general public's concerns about religious extremism. Indeed, if anything, Muslims may be more concerned than non-Muslims about extremism in the name of Islam. Still most Muslims say there is lilliputian support for extremism within the U.S. Muslim community, and few say they recollect violence against civilians can be justified in pursuit of religious, political or social causes.

Muslims concerned virtually extremism, both globally and in U.S.

Overall, eight-in-ten Muslims (82%) say they are either very concerned (66%) or somewhat concerned (16%) about extremism in the proper noun of Islam effectually the globe. This is similar to the per centum of the U.S. general public that shares these concerns (83%), although Muslims are more probable than U.S. adults overall to say they are very concerned about extremism in the name of Islam around the globe (66% vs. 49%).

About seven-in-ten Muslims – and a similar share of Americans overall – are concerned about extremism in the name of Islam in the U.Southward., including roughly one-half of U.S. Muslims (49%) who say they are very concerned about domestic extremism.

Among both Muslims and the larger U.S. public, business organisation about extremism around the world is higher now than it was in 2011 (encounter Chapter 5 for details on trends over time).

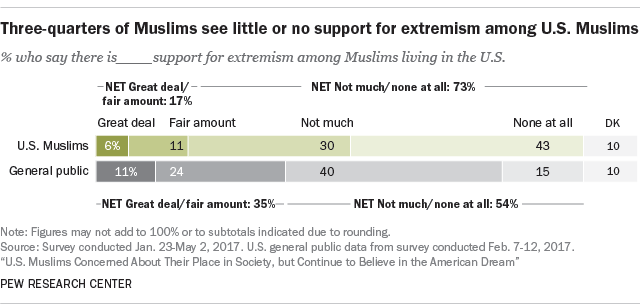

While business about extremism has risen, at that place is lilliputian change in perceptions of how much support for extremism exists among Muslims in the U.s.. Nigh three-quarters of U.S. Muslims (73%) say there is trivial or no back up for extremism amidst American Muslims, while nearly one-in-half-dozen say at that place is either a "off-white amount" (xi%) or a "great deal" (half dozen%) of support for extremism within the U.S. Muslim community.

The overall American public is more than divided on this question. While 54% of U.S. adults say there is little or no back up for extremism among Muslim Americans, roughly a third (35%) say there is at to the lowest degree a "fair amount" of bankroll for extremism amongst U.S. Muslims, including eleven% who think there is a "bully bargain." (For more information nigh how the U.S. public views Muslims and Islam, encounter Chapter 7.)

When is killing civilians seen equally justifiable?

To better understand what some people had in mind when answering this question about targeting and killing civilians for political, social or religious reasons, Pew Inquiry Center staff called back a small number of respondents and conducted non-scientific follow-up interviews. Many respondents – both Muslims and not-Muslims – who said violence confronting civilians can sometimes or often exist justified said they had in mind situations other than terrorism, such equally war machine action or self-defense. For more details on this question, run into Affiliate 5.

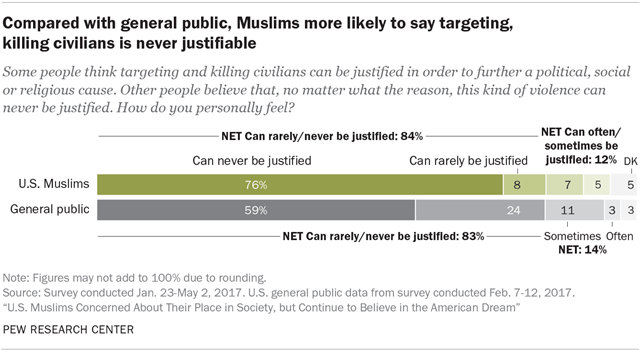

When asked whether targeting and killing civilians can be justified to further a political, social or religious crusade, 84% of U.Due south. Muslims say such tactics can rarely (8%) or never (76%) be justified, while 12% say such violence tin can sometimes (7%) or frequently (5%) be justified.

This question was designed to be asked of the general public also. Compared with the U.S. public as a whole, Muslims are more likely to say targeting and killing civilians for political, social or religious reasons is never justifiable (76% vs. 59%). Roughly equal shares of Muslims (5%) and Americans as a whole (3%) say such tactics are oft justified (the difference betwixt these numbers is non statistically meaning).1

While U.S. Muslims are concerned about extremism and overwhelmingly opposed to the use of violence against civilians, they also are somewhat mistrustful of constabulary enforcement officials and skeptical of the integrity of government sting operations. Almost four-in-ten U.S. Muslims (39%) believe most Muslims who have been arrested in the U.South. on suspicion of plotting terrorist acts posed a real threat. But three-in-10 (xxx%) say police force enforcement officers have arrested mostly people who were tricked and did non pose a existent threat. And an boosted iii-in-ten volunteer that "it depends" or offering another response or no response. Views on this topic amidst the full general public are less divided: A majority of U.S. adults (62%) say officers in sting operations have mostly arrested people who posed a real threat to others.

Meanwhile, about a tertiary of Muslim Americans say they are either very worried (15%) or somewhat worried (20%) that the government monitors their phone calls and emails because of their religion. Yet, on a different question – which does non mention religion – Muslims really are less likely than Americans overall to call up the regime is monitoring them: Near half dozen-in-10 Muslims (59%) say it is either very likely or somewhat likely that the authorities monitors their communications, compared with 70% of the general public.

Roughly half of Muslims say they have experienced recent bigotry

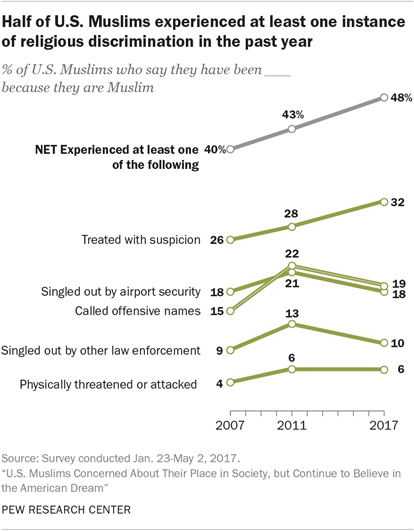

In addition to gauging broad concerns almost discrimination, the survey also asked Muslims whether they personally accept experienced a few specific kinds of discrimination within the past twelvemonth. The share of U.S. Muslims who say they have faced at least one of these types of bigotry has risen modestly in recent years.

In addition to gauging broad concerns almost discrimination, the survey also asked Muslims whether they personally accept experienced a few specific kinds of discrimination within the past twelvemonth. The share of U.S. Muslims who say they have faced at least one of these types of bigotry has risen modestly in recent years.

About a third of Muslims, for case, say they accept been treated with suspicion over the past 12 months considering of their religion. Nearly one-in-five say they accept been called offensive names or singled out past airport security, while one-in-ten say they have been singled out past other law enforcement officials. And half dozen% say they take even been physically threatened or attacked.

In total, most one-half of Muslims (48%) say they have experienced at least one of these types of discrimination over the past year, which is upwardly slightly from 2011 (43%) and 2007 (twoscore%). In addition, nearly ane-in-five U.S. Muslims (xviii%) say they accept seen anti-Muslim graffiti in their local community in the last 12 months.

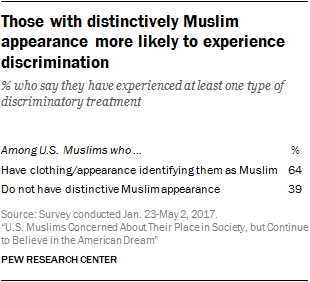

Experiences with discriminatory treatment are specially mutual amongst those whose advent identifies them as Muslim. Overall, about 4-in-10 Muslims (38%) – including half of Muslim women (49%) – say that on a typical day, there is something distinctive almost their appearance, voice or clothing that people might associate with Muslims. Of those whose appearance is identifiably Muslim, almost two-thirds (64%) say they have experienced at least one of the specific types of bigotry asked virtually in the survey. Amongst Muslims who say they exercise not have a distinctively Muslim advent, fewer study these types of experiences (39%).

Experiences with discriminatory treatment are specially mutual amongst those whose advent identifies them as Muslim. Overall, about 4-in-10 Muslims (38%) – including half of Muslim women (49%) – say that on a typical day, there is something distinctive almost their appearance, voice or clothing that people might associate with Muslims. Of those whose appearance is identifiably Muslim, almost two-thirds (64%) say they have experienced at least one of the specific types of bigotry asked virtually in the survey. Amongst Muslims who say they exercise not have a distinctively Muslim advent, fewer study these types of experiences (39%).

While roughly half of Muslims say they have experienced a specific instance of discrimination over the past twelvemonth, a similar share (49%) say someone has expressed back up for them considering they are Muslim in the past 12 months. The percent of U.S. Muslims who study this type of experience is upwards significantly since 2011 (37%) and 2007 (32%).

In their ain words: What Muslims said near discrimination and support

Pew Research Heart staff called back some of the Muslim American respondents in this survey to get additional thoughts on some of the topics covered. Here is a sampling of what they said nearly their experiences with discrimination and the expressions of support they have received:

"I accept definitely experienced both [discrimination and support]. I've had people make comments and of grade they'll give me weird looks and things like that. Merely I've definitely heard people [make] rude comments straight to my confront. I've also had people say actually nice things about my hijab, or say it'south cute or say they think my religion is beautiful." – Muslim woman under 30

"There was a fourth dimension where I used to wearable a veil that covered my face, the niqab, and I take public transportation, and when I was on a bus someone claimed I was a terrorist. I did not know what to do considering no one ever called me that. The person was sitting near me, and I remember getting off the passenger vehicle. No one came to my defense and I did not look anyone to come to my defense. If you lot cover your face, people assume you lot are dangerous. I don't article of clothing the niqab anymore. … I heard a woman took a bus and she wore niqab and got attacked. People were worried for my prophylactic, and I did not want to take a hazard. I wear the hijab [covering the pilus, only not face] now. This happened a year ago and after that I stopped wearing a niqab. Now, I get questions a lot, merely people are not afraid. [When wearing the niqab], people assumed I was not built-in here and don't speak English. Even wearing hijab I get that. Just with hijab, there is marvel but not bigotry." – Muslim woman nether 30

"I have lived in this country for 15 years and have never had a bad experience because of my religion or faith." – Muslim woman over 60

"I accept never experienced discrimination in a direct or targeted way. Things accept been very good. But sometimes I come across someone looking at me funny because of my accent and the manner I await, and information technology makes me a little uncomfortable. But I take a lot of support. Anybody I work with supports me, so I accept many people who can aid." – Muslim man nether xxx

"I have a lot of friends, and just customs members, who are very open – who are glad to accept this kind of diversity in their community, where at that place aren't a lot of Muslims at all. I'm probably the simply Muslim they know or they'll ever know. And they're glad for that, and they like to give support and be at that place." – Muslim man nether 30

"Occasionally [my girl] would say kids make fun of her. Or the kids would ask, 'Are you bald nether hijab?' 'Why don't you lot show your hair?' … [While attending a parade], a couple from [the Southward] engaged my daughter, and my wife was sitting on one demote and my other girl and I were sitting on some other. And she started asking her, 'Does your dad make you wear this?' And my daughter was prepared to respond and said, 'Nope. This is my pick. He supports me. It'southward not required. My mom doesn't vesture it. Only I clothing it because I cull to clothing information technology.' I retrieve those types of experiences are something she goes through, and I think we basically reassure her every time that we get an opportunity: 'This is what you've chosen to do. Now you have called to limited yourself, and we stand up by you 100%. This is America and everyone is free to choose to live the way they cull.'" – Muslim male parent

Muslims leery of Trump

The human relationship between Donald Trump and the U.S. Muslim community has received a lot of media coverage, peculiarly post-obit Trump'southward statement during the campaign that he would seek a "total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States" and his executive order blocking travel from six Muslim-majority countries. ii

The human relationship between Donald Trump and the U.S. Muslim community has received a lot of media coverage, peculiarly post-obit Trump'southward statement during the campaign that he would seek a "total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States" and his executive order blocking travel from six Muslim-majority countries. ii

About three-quarters of Muslim Americans (74%) say the nation's new chief executive is unfriendly toward their grouping, while two-thirds (65%) say they disapprove of the manner Trump is handling his job equally president. U.Due south. Muslim opinion on the sitting president has turned dramatically since 2011, when Muslims expressed much more positive views of Barack Obama.

In 2007, well-nigh the end of his second term, George West. Bush received approving ratings from U.Due south. Muslims that were about every bit low as Trump's today. Respondents in that survey were not asked whether they thought Bush-league was friendly toward Muslim Americans.

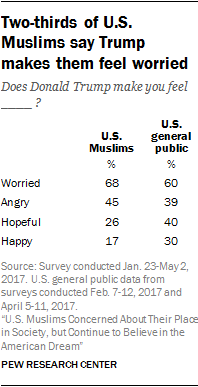

In the new survey, respondents were asked whether Trump makes them feel four emotions – two positive (promise and happiness) and two negative (worry and anger). Fully two-thirds of Muslim Americans (68%) say the president makes them feel worried, and 45% say he makes them feel angry. Far fewer say the president makes them feel hopeful (26%) or happy (17%).

In the new survey, respondents were asked whether Trump makes them feel four emotions – two positive (promise and happiness) and two negative (worry and anger). Fully two-thirds of Muslim Americans (68%) say the president makes them feel worried, and 45% say he makes them feel angry. Far fewer say the president makes them feel hopeful (26%) or happy (17%).

Muslim Americans are less likely than the public as a whole to say Trump makes them experience hopeful (26% vs. 40%) or happy (17% vs. 30%), only well-nigh equally likely to say Trump makes them feel worried or angry.

Muslims proud to be American, just say they face significant challenges in U.S. society

U.S. Muslims limited pride in their religious and national identities alike. Fully 97% agree with the statement, "I am proud to be Muslim." Nearly every bit many (92%) say they agree with the statement, "I am proud to exist an American." In total, 89% hold with both statements, saying they are proud to be Muslim and proud to be American. Merely 6% say they are proud to exist Muslim and not proud to exist American, and 1% say they are proud to be American and not proud to be Muslim.

U.S. Muslims limited pride in their religious and national identities alike. Fully 97% agree with the statement, "I am proud to be Muslim." Nearly every bit many (92%) say they agree with the statement, "I am proud to exist an American." In total, 89% hold with both statements, saying they are proud to be Muslim and proud to be American. Merely 6% say they are proud to exist Muslim and not proud to exist American, and 1% say they are proud to be American and not proud to be Muslim.

At the same time, many Muslims say they face up a variety of significant challenges in making their way in American society. Fully one-half say that information technology has become more difficult to be Muslim in the U.S. in recent years, and an additional 44% say the difficulty or ease of beingness Muslim has not changed very much. Merely 3% volunteer that it has become easier to be Muslim in America.

At the same time, many Muslims say they face up a variety of significant challenges in making their way in American society. Fully one-half say that information technology has become more difficult to be Muslim in the U.S. in recent years, and an additional 44% say the difficulty or ease of beingness Muslim has not changed very much. Merely 3% volunteer that it has become easier to be Muslim in America.

Muslims who say it has become more difficult to be Muslim in the U.S. in recent years were asked to depict, in their own words, the main reasons for this. The most common responses include statements near Muslim extremists in other countries, misconceptions and stereotyping about Islam among the U.S. public, and Trump'due south attitudes and policies toward Muslims. (For full details, see here.)

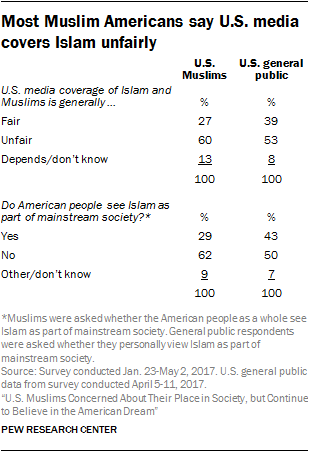

Most Muslims (60%) likewise perceive media coverage of Muslims and Islam every bit unfair, and a similar share (62%) think the American people every bit a whole exercise not encounter Islam as part of mainstream American social club. These views are largely echoed by U.Southward. adults overall, many of whom hold that media coverage of Muslims is unfair and say they personally do non see Islam as function of mainstream order.

Most Muslims (60%) likewise perceive media coverage of Muslims and Islam every bit unfair, and a similar share (62%) think the American people every bit a whole exercise not encounter Islam as part of mainstream American social club. These views are largely echoed by U.Southward. adults overall, many of whom hold that media coverage of Muslims is unfair and say they personally do non see Islam as function of mainstream order.

Only tension is not the but thing that defines the human relationship between Muslims and the residual of the U.Due south. population. Six-in-x U.South. Muslims say they have a lot in common with most Americans. And Muslims are much more likely to say the American people, in general, are friendly toward Muslims in the country (55%) than to view Americans as a whole as unfriendly (14%). (Three-in-10 say Americans are generally neutral toward Muslims.) Moreover, U.S. Muslims have become slightly more likely to view the American public as friendly toward them since 2011, when 48% took this position.

Muslim women more concerned than men about their place in society

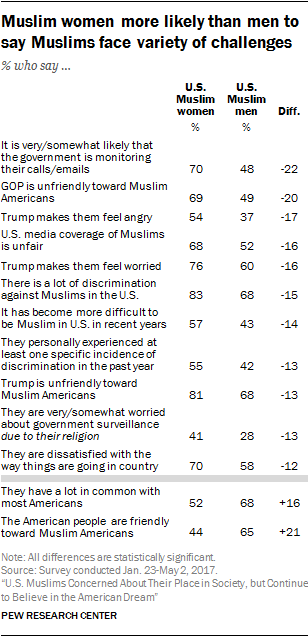

The survey finds a consequent gender gap on several questions almost what information technology is like to exist a Muslim in America, showing that Muslim women have a higher level of concern than Muslim men about the identify of Muslims in U.S. society.

The survey finds a consequent gender gap on several questions almost what information technology is like to exist a Muslim in America, showing that Muslim women have a higher level of concern than Muslim men about the identify of Muslims in U.S. society.

For example, more than Muslim women than men say that there is a lot of discrimination confronting Muslims in the U.Southward. today, that they accept personally experienced discrimination and that it has become more than difficult to exist Muslim in the U.South. in contempo years.

In add-on, more than Muslim women than men say Donald Trump makes them angry or worried, and more women than men say both Trump and the Republican Party are unfriendly toward Muslim Americans.

Muslim women are more likely than Muslim men to say that they are dissatisfied with the fashion things are going in the state and that media coverage of Muslims is unfair. Meanwhile, more Muslim men than women say that they have a lot in common with virtually Americans and that the American people in general are friendly toward Muslim Americans.

In their ain words: What Muslims said well-nigh their place in America

Pew Enquiry Center staff called back some of the Muslim American respondents in this survey to become additional thoughts on some of the topics covered. Here is a sampling of what they said about what it is similar to exist a Muslim in the United States in 2017:

"Ane of the things I noticed as I was going through this [survey] procedure … as a upshot of things [such equally] … Muslims spying on our own population, electronic monitoring, the Muslim lists, I noticed I was really self-censoring. I was very nervous about providing the feedback initially. … Information technology's i of those underlying subliminal things that only happens. Because you feel like you're in a constant state of nervousness. … It'south something that is prevalent across the customs." – Immigrant Muslim man

"I don't really experience similar I have a lot in common with most Americans. Information technology depends on their upbringing, their race, everything like that. I think that we have a lot of different ethics, and we believe a lot of dissimilar things. … Then I exercise feel a lot different, a sense of not fitting in as much." – Muslim woman under 30

"What I have in mutual with most Americans is a dedication to this land. We also take in common our shared humanity. … Nosotros're all struggling to earn, pay our taxes and raise our kids. More and more, I'm finding it hard to find mutual ground with people who don't understand minority communities. The minorities are becoming the bulk, and I know that'south hard for some people. I feel sympathy for them; empathy every bit well. But they demand to accept this new reality." – Muslim adult female in her 40s

"There is so much attending fatigued to people existence Muslim and symbols of Islam, hijab beingness one of them. Nosotros have to take actress circumspection scanning our surround – know where nosotros are, who is effectually and what kind of thoughts they might hold for Islam, almost Islam or against Islam. Particularly when the Muslim ban was introduced the first time around, I literally felt like the persecution had started. Because we had read the history of Europe and what happened to the Jewish people in Germany. These little steps lead to bigger issues later on. So, we really felt like nosotros were threatened. And, fortunately, the justice system stopped implementation. And later on on people stopped talking nigh it, and after a while it seemed like things might exist getting amend." – Immigrant Muslim human being

"I see some immigrants – and not only Muslims, they could be Latinos besides – who don't adapt well to their new state and don't want to be part of American society. They stick with others similar themselves because they're afraid and feel strange here. Merely that's not me. I am completely American, and I experience at home here. When I first came here, I went to high school and that helped me to become more fully American and to adapt to the culture. I feel like I accept a lot in common with the people I run into and know here, and I feel completely comfy hither. When you make it in America every bit an immigrant, you have to allow your past go, or else you won't exist able to become a part of your new country." – Muslim man under 30

"I'd say it'south been increasingly hard, really. Yous most get that post-nine/11 temper in the United States considering of the suppression, actually, of minorities and minorities' thoughts and voices. People like the alt-correct or ultraconservative Trump supporters now have a larger vox that was suppressed just years ago, and now they're really allowed to make heard what they call back about Muslims and minorities in full general. So information technology's a lot of tensions have been rising and fears that we're going backward." – Muslim human under 30

Muslim demographics: A diverse and immature population

Muslims represent a relatively small but rapidly growing portion of the U.S. religious landscape. Pew Inquiry Centre estimates that in that location are 3.45 million Muslims of all ages living in the U.Due south. – upwardly from about 2.75 million in 2011 and 2.35 million in 2007. This means Muslims currently make up roughly ane.1% of the U.South. population. 3 (For more than data about how many Muslims live in the U.Southward. and well-nigh how Pew Research Middle calculates these figures, see Affiliate one.)

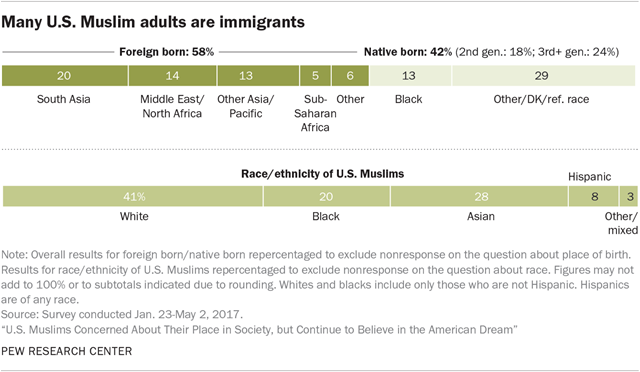

Muslim Americans are largely an immigrant population: Roughly six-in-ten U.S. Muslims ages 18 and over (58%) were born outside the U.Southward., with origins spread throughout the earth. The well-nigh common region of origin for Muslim immigrants is Southern asia, where ane-in-five U.South. Muslims were built-in, including 9% who were born in Pakistan. An boosted 13% of U.S. Muslims were born elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific region (including Iran), 14% in the Centre E or North Africa, and five% in sub-Saharan Africa.

Due in no small part to their wide range of geographic origins, U.S. Muslims are a racially and ethnically diverse population. No single racial group forms a majority, with about 4-in-ten Muslim adults (41%) identifying as white (including Arabs and people of Eye Eastern ancestry), 28% identifying as Asian (including people of Pakistani or Indian descent) and 1-in-v identifying as blackness or African American.

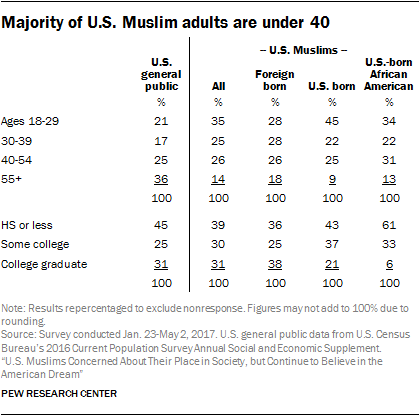

The data likewise testify that Muslim Americans are a very young group. Nearly Muslim adults (60%) are under the historic period of 40. Past comparison, just 38% of the U.South. adult population as a whole is younger than twoscore.

The data likewise testify that Muslim Americans are a very young group. Nearly Muslim adults (60%) are under the historic period of 40. Past comparison, just 38% of the U.South. adult population as a whole is younger than twoscore.

3-in-ten Muslims (31%) are college graduates, which is on par with the share of U.S. adults as a whole who have completed higher. But Muslim immigrants are, on average, more highly educated than both U.S.-built-in Muslims and the U.Due south. public as a whole. (For more on the demographics of the U.Due south. Muslim population, run into Chapter one.)

Muslims say their religion is non only about beliefs and rituals

The diversity of Muslims in the U.S. extends to religious beliefs and practices as well. While nearly all Muslims say they are proud to be Muslim, they are non of i listen about what is essential to being Muslim, and their levels of religious practice vary widely.

Nearly U.S. Muslims (64%) say in that location is more than one true way to translate Islam. They also are more likely to say traditional understandings of Islam demand to exist reinterpreted in lite of modern contexts (52%) than to say traditional understandings are all that is needed (38%).

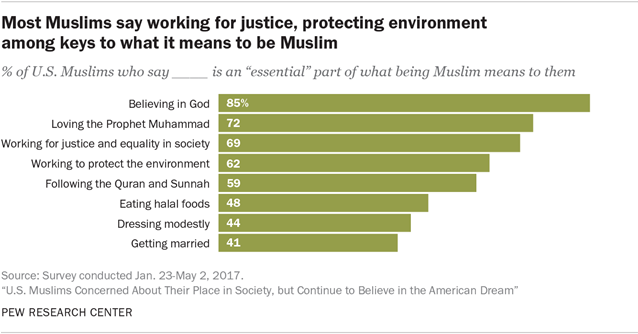

Muslims also were asked whether each of eight actions and behaviors is an "essential" part of what being Muslim means to them, an "important but not essential" part or "not an of import" part. Fully 85% of Muslims say assertive in God is essential to what being Muslim means to them, more than than say the aforementioned about any other item in the survey. And nearly three-quarters say "loving the Prophet Muhammad" is essential to what being Muslim ways to them.

Yet many U.S. Muslims say that for them, personally, being Muslim is virtually more than than these core religious behavior. Roughly seven-in-ten, for instance, say "working for justice and equality in gild" is an essential part of their Muslim identity, and 62% say the same about "working to protect the environment" – which is higher than the share of U.S. Christians who said protecting the environment is essential to their Christian identity in response to a similar question (22%).

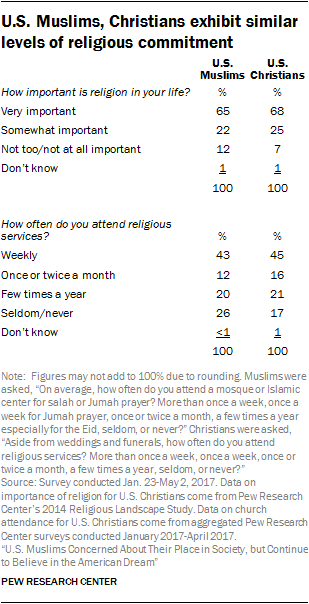

In other ways, though, U.Due south. Muslims look similar to U.South. Christians – on boilerplate, the two groups bear witness roughly equal levels of religious commitment. About ii-thirds of U.Southward. Muslims (65%), for example, say organized religion is very important in their lives, as do 68% of Christians, co-ordinate to Pew Research Center'south 2022 Religious Landscape Study. And 43% of Muslim Americans say they attend a mosque on a weekly basis, on par with the 45% of U.South. Christians who have described themselves as weekly churchgoers in recent surveys. Another 12% of U.S. Muslims say they go to a mosque monthly, and i-in-five (twenty%) say they go to a mosque a few times a yr, especially for important Muslim holidays such equally Eids.4 (For more information on Eid and other terms, see the glossary.)

In other ways, though, U.Due south. Muslims look similar to U.South. Christians – on boilerplate, the two groups bear witness roughly equal levels of religious commitment. About ii-thirds of U.Southward. Muslims (65%), for example, say organized religion is very important in their lives, as do 68% of Christians, co-ordinate to Pew Research Center'south 2022 Religious Landscape Study. And 43% of Muslim Americans say they attend a mosque on a weekly basis, on par with the 45% of U.South. Christians who have described themselves as weekly churchgoers in recent surveys. Another 12% of U.S. Muslims say they go to a mosque monthly, and i-in-five (twenty%) say they go to a mosque a few times a yr, especially for important Muslim holidays such equally Eids.4 (For more information on Eid and other terms, see the glossary.)

The survey also shows that eight-in-ten Muslim Americans say they fast during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. And roughly four-in-10 Muslims (42%) say they pray all v salah daily, with another 17% saying they make some of the 5 salah each mean solar day. (Salah is a form of ritual prayer or observance performed throughout the day, and praying salah is one of the 5 Pillars of Islam. For more than information, see the glossary.)

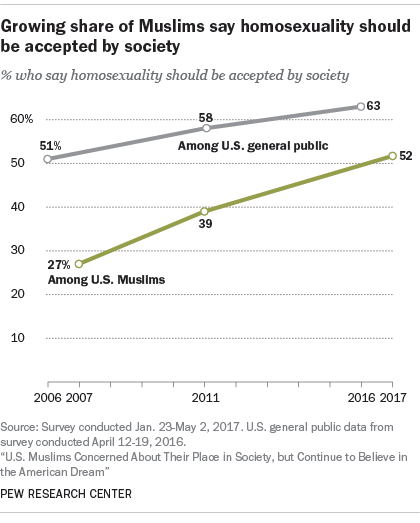

American Muslims, like the U.S. public as a whole, have become much more accepting of homosexuality in recent years. In the first Pew Inquiry Center survey of Muslims, in 2007, far more than Muslims said homosexuality should be discouraged by order (61%) than said information technology should be accepted (27%). By 2011, Muslims were roughly evenly separate on this question. Today, Muslims who say homosexuality should exist accustomed past society clearly outnumber those who say information technology should be discouraged (52% vs. 33%).

American Muslims, like the U.S. public as a whole, have become much more accepting of homosexuality in recent years. In the first Pew Inquiry Center survey of Muslims, in 2007, far more than Muslims said homosexuality should be discouraged by order (61%) than said information technology should be accepted (27%). By 2011, Muslims were roughly evenly separate on this question. Today, Muslims who say homosexuality should exist accustomed past society clearly outnumber those who say information technology should be discouraged (52% vs. 33%).

While Muslims remain somewhat more than conservative than the general public on views toward homosexuality, they are more ideologically liberal than U.S. adults overall when it comes to immigration and the size of government. About eight-in-ten U.S. Muslims believe that immigrants strengthen the country with their hard work and talent (79%), which is perhaps non surprising, given that most Muslims are themselves immigrants. And two-thirds of Muslim Americans (67%) say they prefer a larger authorities that provides more than services over a smaller government that provides fewer services.

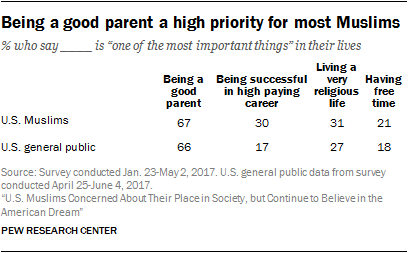

On some other issues, the views of U.S. Muslims mirror those of the larger public. Similar Americans overall, virtually Muslims rank being a good parent as "ane of the most important things" in their lives, and they tend to rate having a successful career and living a very religious life equally at least somewhat important just not necessarily amongst the most important things in life.

On some other issues, the views of U.S. Muslims mirror those of the larger public. Similar Americans overall, virtually Muslims rank being a good parent as "ane of the most important things" in their lives, and they tend to rate having a successful career and living a very religious life equally at least somewhat important just not necessarily amongst the most important things in life.

Political preferences: Muslims are strongly Democratic

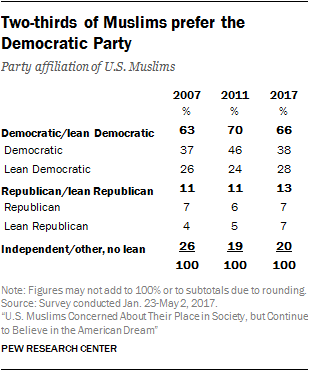

Two-thirds of U.S. Muslims either identify every bit Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party; far fewer (13%) identify as Republican or lean toward the GOP. Muslims favored the Autonomous Political party over the GOP by comparable margins in both previous Pew Inquiry Center surveys.

Two-thirds of U.S. Muslims either identify every bit Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party; far fewer (13%) identify as Republican or lean toward the GOP. Muslims favored the Autonomous Political party over the GOP by comparable margins in both previous Pew Inquiry Center surveys.

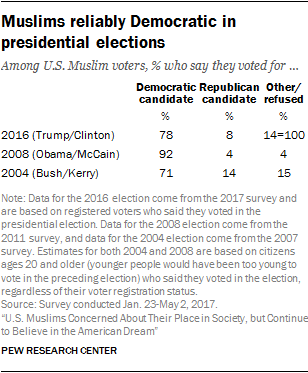

When asked how they voted in concluding year'southward presidential election, three-quarters of Muslim voters (78%) say they backed Hillary Clinton, viii% say they voted for Trump, and 14% say they voted for another candidate or decline to say how they voted. Clinton's lxx-bespeak margin of victory over Trump amidst Muslims falls brusk of Barack Obama'south margin over John McCain; in the 2011 survey, 92% of U.S. Muslim voters said they cast ballots for Obama in 2008, compared with only iv% who reported voting for McCain. In 2007, 71% of U.Southward. Muslims said they voted for John Kerry in 2004, compared with 14% who voted for George W. Bush.

When asked how they voted in concluding year'southward presidential election, three-quarters of Muslim voters (78%) say they backed Hillary Clinton, viii% say they voted for Trump, and 14% say they voted for another candidate or decline to say how they voted. Clinton's lxx-bespeak margin of victory over Trump amidst Muslims falls brusk of Barack Obama'south margin over John McCain; in the 2011 survey, 92% of U.S. Muslim voters said they cast ballots for Obama in 2008, compared with only iv% who reported voting for McCain. In 2007, 71% of U.Southward. Muslims said they voted for John Kerry in 2004, compared with 14% who voted for George W. Bush.

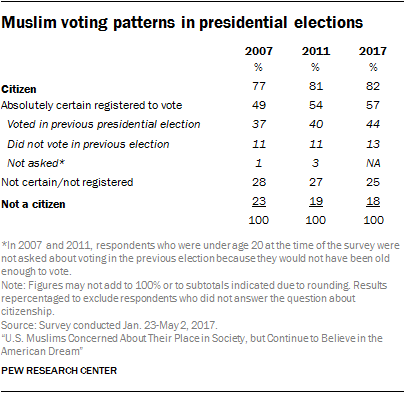

Overall, 44% of U.Due south. Muslims say they voted in the 2022 ballot.five Nearly i-in-5 Muslim adults living in the U.Southward. (eighteen%) are not U.S. citizens, and thus not eligible to vote. In improver, ane-in-four Muslims are citizens only are non registered to vote (25%), and 13% of Muslims are registered voters who stayed domicile on Election Day.6

Overall, 44% of U.Due south. Muslims say they voted in the 2022 ballot.five Nearly i-in-5 Muslim adults living in the U.Southward. (eighteen%) are not U.S. citizens, and thus not eligible to vote. In improver, ane-in-four Muslims are citizens only are non registered to vote (25%), and 13% of Muslims are registered voters who stayed domicile on Election Day.6

Two-thirds of Muslims (65%) say they practise not remember there is a natural conflict between the teachings of Islam and democracy, while three-in-x say there is an inherent conflict between Islam and democracy.

Those who say at that place is a disharmonize were asked to explain, in their own words, why they call back Islam and republic clash. Some say that Islam and democracy have fundamentally incompatible principles and values (twoscore% of those who say there is a conflict), others say the apparent conflict is because non-Muslims don't understand Islam or because terrorists requite Islam a bad name (16%), and however others say democracy is incompatible with all faith (ix%). (For more details on responses to these questions, see Chapter 4.)

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/07/26/findings-from-pew-research-centers-2017-survey-of-us-muslims/

0 Response to "Make America Great Again Muslim Head Scarf"

Enregistrer un commentaire